VENICE: Venice International Film Festival title “Nezouh,” which means displacement or migration in Arabic, sees director Soudade Kaadan present an allegorical tale of female emancipation set during the height of the Syrian conflict in Damascus.

In some ways Kaadan’s latest feature is an extension of her debut film, “The Day I Lost My Shadow,” which clinched the Lion of the Future Award at the festival in 2018. Both employ folklore and magic realism to explore civil strife in her country, however her new work is a far more complex study of a hopeless situation faced by a small family.

The movie examines how the war changed culture and societal norms. She said in released statement about her film that “it is only after the bombing started in my neighborhood in Damascus that I left the house in late 2012. Damascene society was really closed even in liberated families. Women were allowed to travel, work, study, everything but to live alone. With the new wave of displacement, it’s became normal for the first time to see young Syrian women living alone and separating from their families.”

‘Nezouh’ examines how the war changed culture and societal norms. (Supplied)

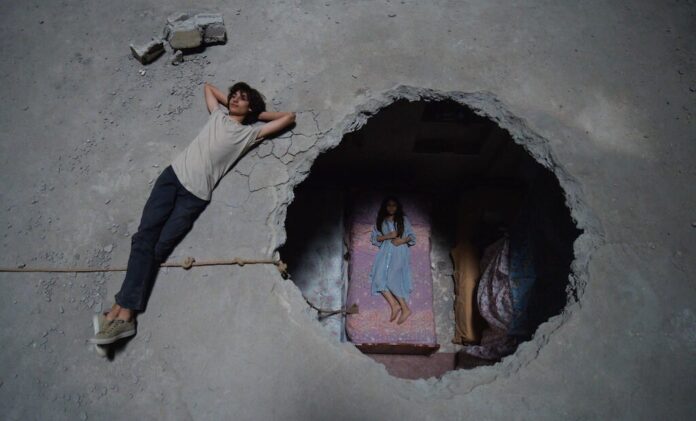

It is against this backdrop that the director weaves a heartrending story of the angst of being uprooted, male patriarchy and obstinacy. Fourteen-year-old Zeina (Hala Zein) and her parents –mother Hala (Kinda Aloush) and father Motaz (Samir Al-Masri) — are the last inhabitants of their war-ravaged neighborhood. While her father is dead set against moving out to become part of the hundreds of thousands of refugees, his wife and daughter want to leave due to failing electricity and a scarcity of water and food. In the beginning, Hala is passive, submitting to her husband’s unreasonable whims. Even when a bomb rips through their apartment, Motaz does not give up, forcing his family to lead a dangerous life. It is only later that Hala uses her pluck, courage and imagination to slip out of a desperate situation.

Kaadan, who also wrote the screenplay, keeps the narrative light without weighing it down with darkness and depression. There is humor and despite Motaz’s dogmatic attitude, he gets a smile out of Zeina and Hala. Also, what turns out to be an interesting offshoot of the story is an innocent relationship that develops between Zeina and a neighborhood lad, Amir (Nizar Alani). A lovely relationship ensues, and Kaadan implies that all is not lost.

Multiple moments of visual delight have been captured by Helene Louvart and Burak Kanbir. The sun-drenched images of a destroyed Damascus look surreal with gentle music adding to the sense of unyielding human spirit.