DUBAI: Malaeen Luqman Khalaf was in her early teens when Daesh swept into Iraq and unleashed a genocidal campaign against the Yazidis, an ancient ethnic and religious minority living in the country’s north-west. A young girl of just 14, she was among thousands of Yazidi women and adolescent girls who were kidnapped and enslaved. Many of them were systematically raped and subjected to horrific acts of sexual violence. Thousands of men were also murdered and hundreds of thousands of Yazidis were forced to flee their ancestral homelands.

The fate of many of those women and girls remains unknown, but Yazda, a community-led organization that protects and champions religious and ethnic minorities in Iraq, Iraqi Kurdistan and Syria, has kept a database of survivors since 2014. That database currently numbers more than 1,000.

“The experiences of these women are unimaginable. First, they were under siege. Second, their fathers or brothers or husbands or sons were killed. Third, they were taken as hostages and sold and bought by Isis members and tortured physically and sexually,” says Haider Elias, the president of Yazda, using another term for Daesh. “It’s beyond comprehension.”

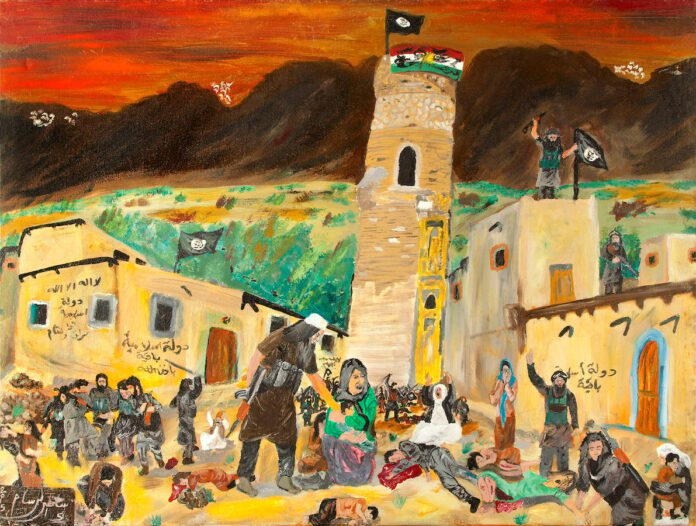

‘Behind Every Darkness is Light’ by Malaeen Luqman. (Supplied)

Now, eight years later, Khalaf is among 16 Yazidi women who have shared their stories of resilience and are using art as a means to support their psychological wellbeing. Working in collaboration with Yazda, the women have created four online exhibitions — collectively known as the Yazidi Cultural Archives — in an attempt to raise awareness of the continued plight of the Yazidis, to conserve their cultural heritage, and to provide psychosocial support. The exhibitions include first-person testimonies, art and photography.

Designed to leverage the psychological benefits of artistic engagement, cultural validation and group support, the archives took a year to create and were launched at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris and at Yazda’s headquarters in Duhok, Iraq, on Oct. 26. They will act as “a permanent digital repository of Yazidi culture” and have been published by the United Nations on Google’s Arts and Culture platform.

Now 23 and living in Qadia camp, Khalaf is in her final year of high school and dreams of becoming an artist. Still too traumatized to discuss her experience, she painted because she wanted people to know what her life was like, both in captivity and after. “I drew the reality of when I was in captivity and after I was free, so the two of them kind of combined, which was hard for me because I had to remember all the things in the past,” she says, speaking through an interpreter. “It helped me to not lose hope, to get up and to work on our culture.”

Deq Tattooing process, photographed by Zina Ibrahim. (Supplied)

“It’s not a conventional archive,” explains Elias, whose brother was killed during the genocide and whose father was briefly abducted. “It’s an archive that has been made by the survivors themselves, with a little bit of help from Yazda and partners.” Those partners include the Iraq Cultural Health Fund, which was established by Community Jameel and Culturunners in 2021, and the Office of the UN Secretary-General’s Envoy on Technology.

For Elias, the project has three primary benefits. The first is the healing and psychosocial support that art can provide to the 16 women from internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in Qadia, Khanke, Mamrashan, Kabartu, Sharia and Chameshko in Duhok Province. An evaluation of the impact of the archives on the psychological wellbeing of participants will be supported by New York University’s Arts and Health initiative and by the World Health Organization’s Arts and Health program.

The second benefit is cultural preservation in the face of continued displacement, while the third is increased global awareness of the continued suffering of the Yazidis, particularly the survivors.

‘Fleeing on truck’ by Zmnanko Ismael. (Supplied)

“What is new in this platform is that there are two levels,” says Nathalie Bondil, head of museum and exhibitions at the IMA. “First of all, the women were able to express what they felt thanks to drawings or paintings. This is the first step of the therapy. But what is also important is that they will be recognized for who they are as women — as women with a name, as individuals. The platform will not only show their drawings but present a portrait of each of them. It will help them to be recognized for who they are — not only to express what they felt or what they endured, but to show who they are to the world.”

At the heart of the project is cultural preservation. Yazidi shrines, temples and other sites of historic importance were destroyed in Sinjar, Bahzani, Bashiqa and elsewhere in northern Iraq. Elias states that around 68 temples were destroyed in Sinjar alone, not only impacting the Yazidis’ tangible heritage but their ability to perform religious rituals and practices. The displacement of hundreds of thousands of people has also created an existential threat to the population’s traditional ways of life. Of the more than half a million Yazidis in Iraq before 2014, 360,000 were displaced by Daesh, with an estimated 200,000 still living in IDP camps. An estimated 2,763 Yazidis are still missing.

“We have a generation of Yazidis who were born in the camps,” says Elias. “We have a generation who do not know what the Yazidi temples are, what the traditional holidays are, what traditional materials we use. A lot of Yazidis are losing this in the camps, especially those who are migrating to Europe. They are assimilating and they forget. Their children are forgetting what the culture of the Yazidis is.”

‘Burning women’ by Hanna Hassan. (Supplied)

During the creation of the archive Khalaf focused on painting but was also drawn to filiklor, a musical style in the stan tradition that tells stories of love, history and religion.

“We would visit people and we would ask them to tell us the stories of these songs and why they sang them, because for us the songs are true stories from the past,” she says. “I just wanted to know more about our traditions and customs after I was freed.” Those traditions include tattooing (known as deq), various forms of cuisine, and national dress.

Then there’s awareness. Because eight years have passed since the genocide, and because other crises have arisen, the suffering of the Yazidis has slipped from public consciousness. “You know, we’ve tried — in terms of advocacy — almost every front,” says Elias, who has also worked with the Nobel Peace Prize winner Nadia Murad, who advocates for survivors of genocide and sexual violence. “We’ve tried virtual reality advocacy; we’ve tried documenting the genocide; we’ve tried advocating conferences in a conventional way. Now we’re trying art because we’ve disappeared from the headlines.

“People’s attention gets divided,” he admits. “The attention of donors and supporters is drawn to more urgent causes, but our problem is that the Yazidi case has not been resolved yet. Nothing has happened. Security hasn’t been achieved. Isis is defeated temporarily, but people have not gone back to their homes, reparation hasn’t started yet, justice has partially started but not completely, and reconciliation hasn’t started. So many aspects are still left hanging there. That’s why it’s important to keep it in the public domain and remind the world that we’re here. We’re still in the camps. We’re still suffering.”