DUBAI: Ten years have passed since demonstrations swept across the streets of Syria, leading to an ongoing civil war and a migration crisis that has impacted the course of the world.

Throughout history, artists have been seen as chroniclers of their times and such a notion can be applied to Syria’s contemporary artists, depicting their own interpretation of warfare and its ramifications for their lives. That is the subject of a new exhibition at the Middle East Institute in Washington DC.

“In this Moonless Black Night: Syrian Art After the Uprising,” which runs until July 16, presents conceptual and experimental work from 14 multidisciplinary artists, all of whom live and work in exile as a result of the country’s political instability. The imagery rarely reveals graphic scenes of war, but instead brings to life a more personal and human take on the complexities of the situation in Syria, which was the intention of the show’s curator, arts writer Maymanah Farhat.

“I didn’t want to show images of bodies being pulled from the rubble. If you look at Syrian art in the last 10 years, you’ll find those images,” she tells Arab News. “I understand why artists do it and the need to shock the viewer in order for them to really understand the severity of the situation, because we have become so desensitized to news media. I empathize with that, but for me personally, as someone who has experienced war, I just can’t — and I don’t think that’s the role of art.”

The exhibition’s title is taken from the work of the late Syrian poet Da’ad Haddad, and Farhat believes it is the perfect fit for the overall atmosphere of the show. “If you read the poem, it moves back and forth between a cynical kind of melancholy and small glimmers of hope. I feel like that’s how the last 10 years have been,” she says. “I don’t want to speak for Syrian artists, because that’s not my experience. I’m an outsider to it, but what I can offer is a platform to present these varying views and experiences.”

One of the show’s central themes is the emotionally jarring conditions of migration, prompting a sense of loss and displacement. “We revere artists so much and I think we see them as these invincible people who can survive anything, when really that’s not the case. They’re just like the rest of us,” says Farhat.

The Berlin-based artist and cultural activist Khaled Barakeh showcases a powerful statement on this theme through his 2018 digital print on paper, “I Haven’t Slept For Centuries.” The frenzy of the intense blackness is a culmination of visa stamps, passed checkpoints, and entry or exit denials placed on a page of his passport. “We saw really harsh images coming out of the migrant experience, especially in the Mediterranean, and the backlash — the xenophobia — that people experienced in Europe. What happens when you’re constantly faced with this rejection of not being allowed to leave, not being allowed to enter? I think that’s what Khaled communicates effectively; the violence of these bureaucratic lines,” Farhat says.

Similarly, Connecticut-based artist Mohamad Hafez evokes the burden of forced departure from one’s homeland through his installations of antique luggage containing miniature interiors of rooms — a concise portrayal of the concept of living out of a suitcase.

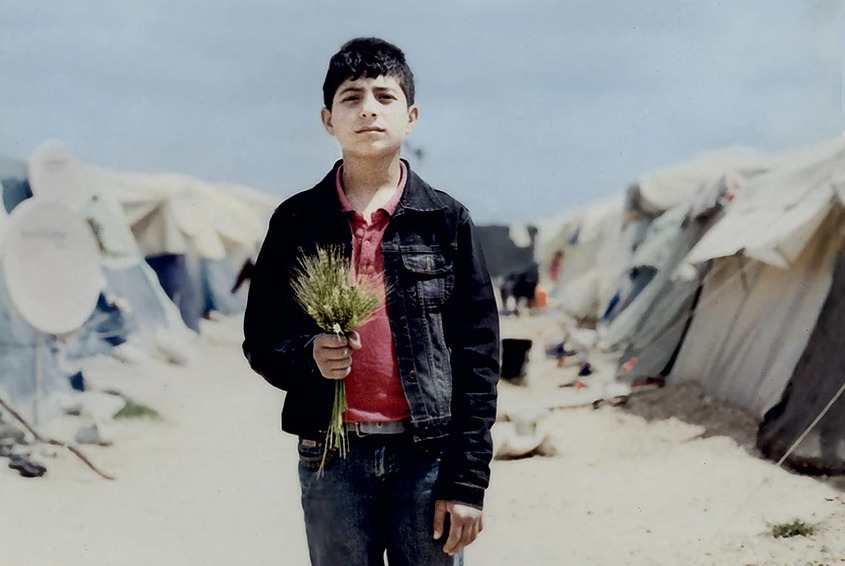

On the other hand, a touch of humanity emerges from Osama Esid’s photographic portraits of children in Turkey’s refugee camps. With his direct but innocent gaze, an element of gentleness is expressed by a young boy, Waleed.

The devastating physical destruction of Syrian homes and cultural monuments over the past tumultuous decade is brought to viewers’ attention a number of times, most notably in the work of the well-known multimedia artist Tammam Azzam. He finds beauty amidst chaos in his emblematic image of Austrian painter Gustav Klimt’s “The Kiss” digitally superimposed on a bullet-riddled building.

One of the exhibition’s strong points is the way in which female artists are thoughtfully included in this dialogue of personal and collective narratives as mothers and daughters. In her “Displacement” series, Oroubah Dieb, who currently resides in Paris, depicts faceless women dressed in ornamented attire, carrying their possessions in pouches on their backs and heads along a migrant trail of men and children.

A touching installation by Essma Imady comes in the form of a teddy bear in a backpack slouching on a pile of salt, reflecting once again the migration crisis and, perhaps, all the lives lost at sea. For this work, entitled “Pillar of Salt,” the Damascus-raised artist spoke with young refugees and was inspired by the biblical tale of Lot’s wife, who was turned into a pillar of salt for disobeying god’s directives and looking back at the destroyed city of Sodom while fleeing.

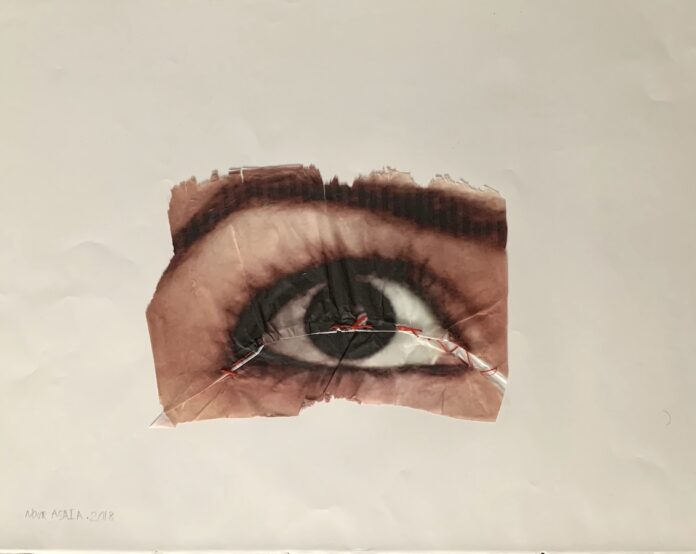

The viewer also experiences female artists as witnesses of violence and its heavy toll on the body. In her Goya-inspired etchings, Azza Abo Rebieh portrays haunting scenes of women in prison, something she personally endured as an imprisoned activist in 2015. And Hama-born Nour Asalia stitches red thread into an image of an eye on rice paper, conveying fragility and vulnerability, as well as bloodshed.

As a result of being displaced abroad, painful as it is, this new generation of Syrian artists have been able to expand their artistry, gain fresh ideas, and experiment with different material. In time, the works of the exhibited artists, and others like them, will surely come to represent a radically bold chapter in Syrian art history.

“This is the first major event that Syrians have had in the last 50 years. It’s devastating: Syria and Syrians have changed forever,” says Farhat, adding that it is the resilience displayed by these artists and their fellow refugees that provides hope for the future.