DUBAI: Valentine’s Day 2023 seems like a timely opportunity to look back on the life of one of the Arab world’s greatest writers, the Lebanese-American poet and painter Gibran Khalil Gibran, who was famous the world over for his touching poetry about love as well as his seminal work, “The Prophet.”

This year marks the 140th anniversary of his birth, as well as the publication of his magnum opus, “The Prophet,” released 100 years ago. After Shakespeare and Lao Tzu, he is reportedly the third best-selling poet of all time.

It is no surprise, when his telling observations on the most powerful of human emotions — love — have become something of a touchpoint in popular culture.

Gibran with a Book, by F. Holland Day. (Supplied)

“Love gives naught but itself and takes naught but from itself. Love possesses not nor would it be possessed; For love is sufficient unto love,” Gibran wrote in “On Love,” in just one example of why he became a key figure in a Romantic movement that transformed Arabic literature in the first half of the 20th century. For Arab readers used to the rigid traditions of Arabic poetry, Gibran’s direct style was a revelation and may have led to his popularity in the Middle East.

As for the Western world, the work for which he is most well-known is without a doubt 1923’s “The Prophet,” which also features such quotable lines on love as: “Love one another, but make not a bond of love: Let it rather be a moving sea between the shores of your souls.”

Gibran, who died in 1931, was 40 years old when “The Prophet” was published in his adopted hometown of New York City by American editor Alfred A. Knopf, the co-founder of his renowned publishing house. He had doubts about how successful Gibran’s book might be.

Glen Kalem-Habib. (Supplied)

Comprised of about 20,000 words, it took Gibran nearly two decades to write this little literary masterpiece, and its impact has lasted for a century, inspiring millions from around the world with its timeless wisdom and meaningful spirituality.

“The Prophet” has been translated into more than 100 languages and has never gone out of print. “I’ve always said that Gibran wrote the first self-help book in the West,” Lebanese-Australian Gibran expert Glen Kalem-Habib told Arab News.

“For me, it’s an evolving story. I think he wrote it in the sense that it grows with you. When you read passages from “The Prophet,” they take on a different meaning depending where you are at, personally, in your life.”

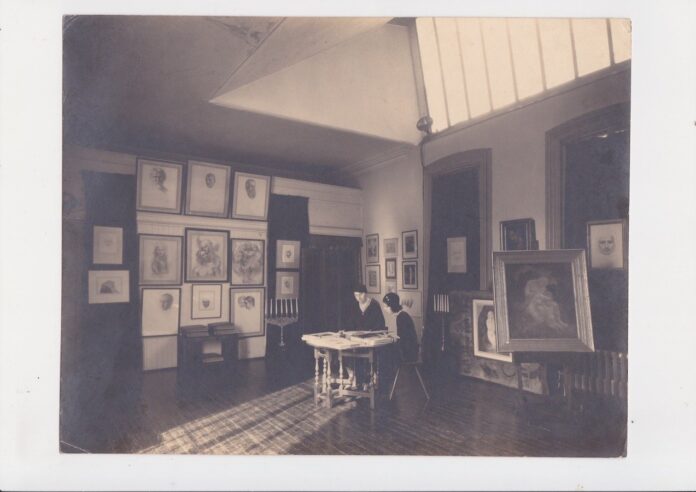

Seated Gibran 1931. (Supplied)

More than ten years ago, Melbourne-based Kalem-Habib founded “The Kahlil Gibran Collective,” which is the world’s largest depository pertaining to all things Gibran. He has made “The Prophet” entirely accessible and downloadable online for reading.

Executed in simple yet profound writing, the story of “The Prophet” begins with Al-Mustafa, “the chosen.” He is leaving the city of Orphalese on a ship that is taking him back to his home of origin after a 12-year separation.

The city’s men and women, youth and scholars, merchants and lawyers ask him about life’s deepest questions. Al-Mustafa taps into more than 20 themes, from love to children, work to freedom, pain to friendship, and pleasure to death.

1st Edition book cover of The Prophet (Public domain). (Supplied)

So where did the idea of “The Prophet” come from? Kalem-Habib believes that a lot of it stems from the author’s childhood, marked by curiosity and imagination. “He had this ambition to be somebody of significance,” he says. “The mystic in Gibran felt that he was born to heal . . . In some innocent way, he wrote one time that, “I’ve always wanted to write a book that heals the world.””

Kalem-Habib also adds that Gibran, who was born in the mountainous and verdant town of Bsharri, Lebanon in 1883, was likely influenced by Middle Eastern culture, history and storytelling. “You think about the backyard that he came from, which dates back thousands of years, and there were some of the biggest figures that we still celebrate: Gilgamesh, the Sumerian and Mesopotamian empires, Alexander the Great and so on,” he explains.

“He grew up with all these mythical figures and archetypes that were so engrained in his imagination. If you peel back some of the characters in “The Prophet,” you’ll find that there are traces of those mythological figures.”

Elvis Presley’s copy of The Prophet with his written notes. (Supplied)

Starting from 1919, the workaholic and perfectionist Gibran devoted many hours to finishing his work, which originally had alternative titles, including “The Commonwealth” and “The Councils.” The now-iconic title of the book was chosen late in the day.

Gibran wrote the text of his piece in both Arabic and English, with the guidance of his benefactress and lover, American editor Mary Haskell, who was 10 years his senior. “He learned to articulate his Arabic thought into English with her help,” explains Kalem-Habib.

“He struggled with the English language. In the end, he mastered it. He was very particular with every single letter . . . He took liberty in capitalizing letters that shouldn’t have been capitalized.”

According to Kalem-Habib, it was Alfred Knopf’s wife, Blanche, who co-founded the publishing firm with him in 1915, that saw potential in Gibran. The two were introduced to each other through a mutual friend. She would go on to collaborate with the likes of Sigmund Freud and Simone de Beauvoir, among others.

1st Ed. Prophet inside cover. (Supplied)

At the price of $2.25, “The Prophet” sold more than 1,000 copies in its first month, which positively surprised Knopf. Kalem-Habib stresses that the book went through gradual success. “It didn’t become popular overnight. It’s been 100 years of popularity,” he explains.

One of the main reasons “The Prophet” resonated with so many readers is because it brought something new to the table, at a time when modern society was materialistic and artificial. Timing was key. “He was the voice of the East, who landed in the West. They were hungry for oriental spirituality. He brought it in with the finesse of a language that’s his own,” Kalem-Habib said.

Its popularity accelerated during the Sixties and Seventies, an era of social and political upheaval. “The sales of The Prophet in those two decades just went through the roof. I don’t think that’s ever been repeated,” he continues. “When the counterculture years were happening, there was a lot of rebellion and anti-war sentiments. It was the authority book on how to live life.”

Gibran in painter’s garment. Colorised by Gibran Collective (Museo Soumaya). (Supplied)

“The Prophet” enjoyed a wide reach, landing on the bookshelves of such giants of Western entertainment as Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe, to name a few.

Even contemporary authors have looked up to Gibran, such as the famed Brazilian novelist Paulo Coelho. “This man, Gibran, he has always been, is, and will be, a reference in my life,” the author of “The Alchemist” once said.

The essential question remains: Why have the verses of “The Prophet” remained so memorable and quotable on special occasions until this day? What is its 100-year secret? Kalem-Habib suggests that its authentic roots in truth has played a role. “My mentor once said to me,” he recalls, “that when you write about verities — those eternal truths — they don’t die.”