LondonL Kim Philby, the notorious Soviet mole who burrowed into the upper echelons of Britain’s Cold War-era intelligence services, was a subject of fear-driven fascination for novelist John le Carré. The two men, Le Carré felt, had far too much in common as upper-class-hating sons of dissolute fathers “so oversized that your only resort as a child was to subterfuge and deceit.”

For Le Carré, Philby’s traitorous life could have been his own.

“I knew, if you like, that Philby had taken a road that was dangerously open to myself, though I had resisted it,” Le Carré wrote in the introduction to a 1991 edition of his “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” novel of deceit, double agents, and moral ambiguity. “I knew that he represented one of the — thank God, unrealised — possibilities of my nature.”

Still, Le Carré was not above subterfuge. As part of the British Foreign Service from 1959 to 1964, Le Carré worked for British intelligence, a role from which he drew fodder for his novels and that necessitated he adopt a pen name to hide his true identity of David Cornwell. Fittingly, after Cornwell was outed and had to leave the service, his real name faded into the shadows as Le Carré became the multimillion-selling novelist whose spy novels transcended the pulp genre to, in the eyes of some critics, literary art.

“He’s a brilliant writer for whom spies are merely subject matter,” Robert Gottlieb, who edited some of Le Carré’s books for Alfred A. Knopf in the 1970s and 1980s, told the New York Times Magazine in 2013. “Calling him a spy writer is like calling Joseph Conrad a sea writer, or Jane Austen a domestic-comedy writer.”

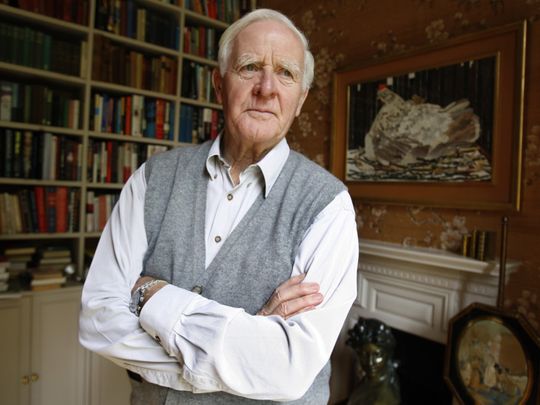

Le Carré died Saturday evening at his home in Cornwall after a short illness, according to a statement from Jonny Geller, CEO of literary agency the Curtis Brown Group. He was 89.

In a career that began in 1961, Le Carré wrote 25 novels ranging from post-World War II espionage in Europe to the post-9/11 struggle against terrorism, with side trips to Panama, Nigeria and Gibraltar, among other places.

Israeli plot

Although best known for his spy stories, he also wrote about Russian money launderers (“Our Kind of Traitor,” 2010), Africans caught up in the turmoil of the Congo (“The Mission Song,” 2006), and a British actress drawn into an Israeli plot to assassinate a Palestinian militant (“The Little Drummer Girl,” 1983).

With fellow Briton Graham Greene, Le Carré helped redefine the spy novel, and showed that, when done well, such works could be read as high art. Le Carré won few literary awards — primarily because he refused to enter the contests and routinely declined nominations. At least seven of his works were adapted to film, beginning with “The Spy Who Came In From the Cold” in 1965 and including the Oscar-nominated “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” in 2011 and “The Constant Gardener” in 2005, for which Rachel Weisz won a best supporting actress Oscar.

Although most spy-genre novels focus on action, Le Carré’s work stood out for his obsession with the gray areas of morality, human weakness and failure, and the machinations of governments — which can become meat grinders for the truth.

“As the systems for propagating information and speeding it around the globe are becoming ever more sophisticated, so do the opportunities to manipulate information,” Le Carré told the Washington Post in 1996. “The manipulation of truth seems to go hand-in-hand with the availability of information.”

Insurance fraud

David Cornwell was born October 19, 1931, in Poole, England, one of two sons of Ronald and Olive Cornwell. His father was a mercurial conman who spent time in prison for insurance fraud but who also connived his way into London’s upper society. It made for a fractious father-son relationship, which found its way into several of Le Carré’s novels and a memoir published in the New Yorker in 2002. Le Carré’s mother ran off with another man when Le Carré was 5, and he spent most of his childhood in boarding schools, an experience that fueled his dislike for the British class system.

Having a knack for languages, Le Carré worked with British army intelligence, interviewing German-speaking defectors from the Eastern bloc, then in 1951 entered Oxford, where he studied modern languages — and worked for MI5, England’s domestic intelligence agency, trying to ferret out Soviet agents.

By 1960, Le Carré was working for MI6, the foreign intelligence service, in Hamburg and Bonn. And he was writing. His first novel, “Call for the Dead,” came out in 1961. His superiors forbade him to publish under his real name, and for reasons that in ensuing years he lied about, obscured or seemed to have forgotten, he came up with the Le Carré pen name.

That first novel also introduced George Smiley, the rotund and unkempt spymaster who would become the main or side character in at least eight of le Carré’s novels. Unlike the most famous literary spy of the era, Ian Fleming’s James Bond, the debonair womanising man of international action, Smiley was a plodding, bureaucratic everyman with a razor-sharp mind, a dogged nature, and an ability to be immediately forgotten.

“He sat leaning back with his short legs bent, head forward, and plump hands linked across his generous stomach,” le Carré wrote in “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.” “His hooded eyes had closed behind the thick lenses. His only fidget was to polish his glasses on the silk lining of his tie, and when he did this his eyes had a soaked, naked look that was embarrassing for those who caught him at it.”

The first two novels received little attention, but le Carré’s third, 1963’s “The Spy Who Came in From the Cold” — a cynical exposition on the moral failing of both the East and the West — was an international best-seller. Le Carré made so much money from the book he stashed away his real-world cloak and dagger and devoted himself to writing to full time.

The fame was overwhelming, and le Carré initially didn’t handle it well. “I made an awful mess of my first marriage,” he said in the New York Times Magazine interview. “It was hard to live with me being me.” He and his wife, Alison, with whom he had three sons — Simon and Stephen, who are involved in film adaptations of le Carré’s novels, and Timothy — divorced in 1971. The next year, he married Valerie Jane Eustace, a former book editor. They had one son together, the British novelist Nick Harkaway.

Honey pot

In his novels, Le Carré sought to mix real terminology from the spy world with invented terms and uses, such as “honey pot” for the use of a pretty woman to seduce a target, “scalphunter” for an assassin, and “lamplighter” for someone who gathers information from surveillance and couriers. Le Carré was surprised to learn that over time many of his invented phrases found their way into the spy world’s lexicon; some even credit him with coining the word “mole” for a highly placed spy, though he said he believed he took the term from the KGB.

But le Carré was foremost a writer of tales that explored human frailty and notions of patriotism, as well as the dehumanising aspects of strict adherence to political doctrine at a time when extremism threatened to plummet the world into nuclear war. “As a storyteller, he’s simply one of the best we have,” Nan Graham, publisher of Scribner, told the Associated Press in 2008.

The embrace was not universal, however. In a 1989 Guardian review of “The Russia House,” author Salman Rushdie dismissed le Carré as a genre writer who wanted to be taken seriously. “Much of the trouble is, I’m afraid, literary,” Rushdie wrote. “There is something unavoidably stick-figure-like about le Carré’s attempts at characterisation.”

The two later descended into a famous literary feud. While deploring the fatwa placed on Rushdie’s head by Iranian spiritual leader Ayatollah Khomeini over perceived slights to Islam in Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses,” le Carré argued in 1997 that “there is no law in life or nature that says great religions may be insulted with impunity.” Le Carré added that he “was more concerned about the girl in Penguin Books who might get her hands blown off in the mailroom than … that Rushdie’s royalties.”

Rushdie responded by calling le Carré “a pompous ass.” It was 15 years before the two reconciled.

Espionage, of course, comes in the service of politics, and le Carré was a persistent critic of post-9/11 US policies and actions. A few weeks before the invasion of Iraq, le Carré wrote a scathing indictment in the Times of London under the headline, “The United States of America Has Gone Mad,” and called the marshaling of public support for war “one of the great public relations conjuring tricks of history.” Le Carré blamed collusion between “US media and corporate interests” for an environment in which, “as in McCarthy times, the freedoms that have made America the envy of the world are being systematically eroded.”

And le Carré saw literature — his literature — as a way to perhaps goad a lethargic body politic to action.

“Every writer wants his book to change people in some way,” he told the Weekly Australian in 2003 after publication of his novel, “Absolute Friends,” about American military globalisation and the fragility of truth. “I want to break through the apathy. I think this book is really saying something that isn’t being said, that we have gone clean off the rails. I hope it entertains. But I also hope it stirs.”

Le Carre is survived by his second wife, Valerie, and his four sons.